Seeds can be very resilient, and in ideal conditions, they can last for hundreds, even thousands of years. However, nature is an unpredictable force, and despite their resilience, seeds can fail to grow in their natural habitat. Seed banks can help store, preserve, and conserve plant species for future generations.

By providing a stable storage enviornment, seed banks can help keep seeds viable for hundreds of years. Seed banks play a strong part in the conservation of native and endangered plants. If a plant were to become extinct in the wild, it could be replanted from stored seeds. Having this outlet allows us to have a positive impact on native plant species. Banked seeds can also be used for habitat restoration or kept for research purposes to help communities nationally and globally. The Bureau of Land Management has the Seeds of Success (SOS) program. It is a cooperative effort between federal and non-federal organizations such as the Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center. This program helps conserve, rehabilitate, and restore lands by using nativeplants. Other entities, such as Britain’s Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, direct international seed banking programs to help communities. The Useful Plant Project uses seed collection, propagation, and reintroduction studies to support the conservation and sustainable use of the most important plants for rural communities in need. For Texas, one recent incident has shown the benefits of seed banking.

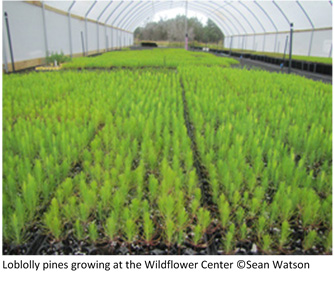

In 2011, Bastrop County experienced the largest wildfire in Texas history. The wildfire destroyed over 34,000 acres of homes, businesses, and the lost loblolly pines. The loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) is native to the eastern region of the United States. However,in the distribution map, you can see a westernmost population in Bastrop County, Texas. That population had become reproductively isolated from the East Texasloblollies (100 miles away), and overmillions of years, the population had become more drought-tolerant. This adaptation made them ideal for the hill country climate unlike East Texas loblollies.

When the wildfire hit Bastrop County, all of the loblolly pines were thought to be completely lost. However, the Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center found out a Texas A&M Forest Service (TFS) employee had been collecting and banking seeds from the lost loblolly pines trees for over 30 years. From the saved seeds the Wildflower Center was able to start loblolly pine nursery consisting of 60,000 replacement trees. Now the center has become a contractor of the TFS, and are growing upwards of 600,000 trees to be planted in Bastrop County. In addition to the 600,000 saplings, the center will grow another 700,000 as a part of a 5-year growing program funded by the Arbor Day Foundation. This story demonstrates the importance of proactive seed collecting and banking, and how it can save plant species. Seed banking can not only protect species from unforeseen events such as wildfires but from invasive species that are entering this country and attacking our native plants.

When the wildfire hit Bastrop County, all of the loblolly pines were thought to be completely lost. However, the Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center found out a Texas A&M Forest Service (TFS) employee had been collecting and banking seeds from the lost loblolly pines trees for over 30 years. From the saved seeds the Wildflower Center was able to start loblolly pine nursery consisting of 60,000 replacement trees. Now the center has become a contractor of the TFS, and are growing upwards of 600,000 trees to be planted in Bastrop County. In addition to the 600,000 saplings, the center will grow another 700,000 as a part of a 5-year growing program funded by the Arbor Day Foundation. This story demonstrates the importance of proactive seed collecting and banking, and how it can save plant species. Seed banking can not only protect species from unforeseen events such as wildfires but from invasive species that are entering this country and attacking our native plants.

There are hundreds of identified invasive animals, plants, and diseases that have wreaked havoc on native plants in the United States. By utilizing seed collection and banking strategies we can try to prevent the impact of an invasive species. Sometimes, it is more of a “damage control” than prevention, but with the accessibility of seed banks, affected species and habitats can actually have a chance at fighting back.

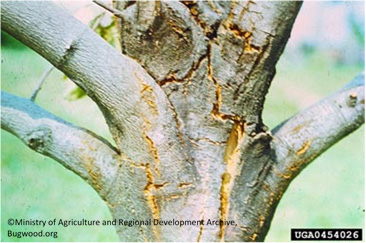

In the early 1900s, a cankerous disease called Chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica) arrived from infected nursery stock imported from Asia. It quickly found a suitable host in the American chestnut. Being a native tree, the American chestnut (Castanea dentata) had such a low resistance to the invasive blight that it was able to kill billions of trees. Research and seed collecting have allowed this tree to have rebirth after the deadly blight. By preserving seeds from surviving trees, entities such as The American Chestnut Foundation, have created blight-resistant trees and reintroduced the trees into native forest habitats. Due to seed bank inventories, other facilities have been able to create hybrids which allows them to continue to do genetic research.

In the early 1900s, a cankerous disease called Chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica) arrived from infected nursery stock imported from Asia. It quickly found a suitable host in the American chestnut. Being a native tree, the American chestnut (Castanea dentata) had such a low resistance to the invasive blight that it was able to kill billions of trees. Research and seed collecting have allowed this tree to have rebirth after the deadly blight. By preserving seeds from surviving trees, entities such as The American Chestnut Foundation, have created blight-resistant trees and reintroduced the trees into native forest habitats. Due to seed bank inventories, other facilities have been able to create hybrids which allows them to continue to do genetic research.

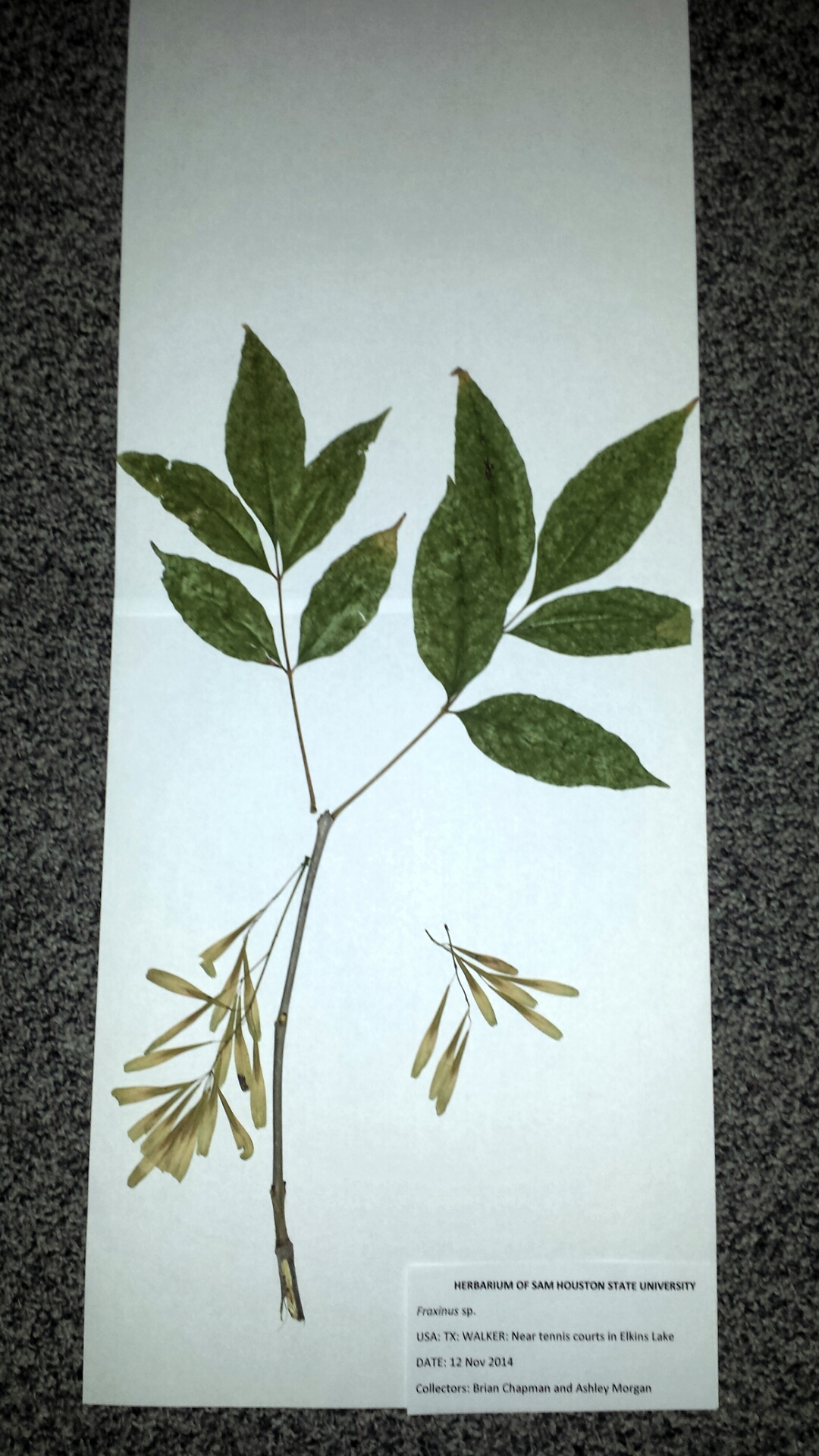

The Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis) is an invasive beetle that came from Asia in the late 1990’s. By 2002, scientists realized that this beetle was behind the widespread damage to Michigan Ash trees. Eight years later, the beetle had spread to 12 states and infested hundreds of thousands of acres. As of the 2014 survey, the beetle is in 25 states, one of which is Arkansas, with quarantined counties right next to Texarkana. With this beetle being able to spread quickly, other states, including Texas, have taken the initiative to start collecting and seed banking all species of ash trees to prevent the complete elimination of them. Researchers have been studying various ash species and their resistance to the emerald ash borer, but all native species seem especially susceptible. Fortunately, the Chinese ash which is from the beetle’s native range has a strong resistance. Further research involving banked seeds will look into hybridization resistance effects, and many other methods to prevent total ash tree elimination.

Literature Cited:

Burnham, D. R., P. A. Rutter, and D. W. French. 1986. Breeding blight-resistant chestnuts. Plant Breed. Rev. 4: 347-397.

Griffin, G. J. 2000. Blight control and restoration of the American chestnut. J. For. 98: 22-27.

Koch, J. L., Carey, D. W., Knight, K. S., Poland, T., Herms, D. A., & Mason, M. E. 2012. Breeding strategies for the development of emerald ash borer-resistant North American ash. In Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on the Genetics of Host–Parasite Interactions in Forestry: Disease and Insect Resistance in Forest Trees (pp. 235-239).

McCullough, D. G., & Katovich, S. A. 2004. Emerald ash borer.

Merkel, H. W. 1905. A deadly fungus on the American chestnut. New York Zool. Soc., 10th Ann. Rep., pp. 97-103.