Hundreds of invasive species are present in the United States and entities like the Texas Invasive Species Institute cannot make any progress on their identification and control without the help of the community. Community outreach allows people to see what we are doing and provides opportunities for TISI to educate others on the threat of invasive species.

In collaboration with Texasinvasives.org, the Texas Invasive Species Institute is starting a Citizen Scientist workshop. Anyone can become a citizen scientist with a fun, one-day workshop! Citizen scientists are volunteers that help slow down the spread of invasive species, and reduce their impact by being another set of eyes in the field. This workshop provides training in identifying and tracking important invaders in our area. In the fight against invasive species early detection is the first step and with help from citizens like you, entities like TISI and texasinvasives.org have a stronger chance of detecting and eradicating invasive species. TISI conducted its first citizen scientist workshop last February and planning for a workshop this year!

In addition to TISI, the Sam Houston Natural History Collections has developed an outreach initiative to engage children and show them that Biology is fun and there’s a lot you can do with it! Every October, Huntsville, Texas puts on a “Scare on the Square” event for the local children. Sam Houston Natural Collections participated by having a “Scary Science” booth. Our community outreach initiative focuses on engaging grade school children in the interesting creatures housed within the collections, all while learning the danger of Invasive Species. In 2014, after contact with a rural high school science teacher a class of students visited the Natural History Collections. The students were able to learn about museum collections and specimens, see the diversity of animals within the collections, invasive species and the impact they can have on food webs. In 2015 the TISI helped the Natural History Collections with education programs in local elementary schools (K-5). Some of the programs focused on food webs, state parks, impacts of invasive species on ecosystems. TISI has also started coordinating with local Boy and Girl Scout troops. By reaching out to our future generations we are hoping to stimulate an interest in STEM classes, and maybe even future Biologists.

Since its inception in late 2011 the Texas Invasive Species Institute (TISI) has strived to meet its goal of Early Detection and Rapid Response in combination with community outreach. Below are some of the grant and outreach programs in which TISI staff have participated over the last three years:

The Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis) is an invasive beetle that came from Asia in the late 1990’s. After a massive ash tree (Fraxinus sp.) dieback in 2002 occurred in Michigan, scientists realized that the EAB was the culprit causing tree loss. By 2014, the beetle had infested hundreds of thousands of acres in 25 states, and has moved westward in Arkansas to the eastern border of Texas. What makes the EAB an even greater threat is that in states where it has become established, is it has been able to attack 6 species of native Fraxinus species. However, another 10 species of Fraxinus could be susceptible to the EAB if it invades states where the other Fraxinus species are native.

The Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis) is an invasive beetle that came from Asia in the late 1990’s. After a massive ash tree (Fraxinus sp.) dieback in 2002 occurred in Michigan, scientists realized that the EAB was the culprit causing tree loss. By 2014, the beetle had infested hundreds of thousands of acres in 25 states, and has moved westward in Arkansas to the eastern border of Texas. What makes the EAB an even greater threat is that in states where it has become established, is it has been able to attack 6 species of native Fraxinus species. However, another 10 species of Fraxinus could be susceptible to the EAB if it invades states where the other Fraxinus species are native.

Following the initial detection of EAB in Michigan, the United States Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA/APHIS) began conducting a survey that has helped detect the EAB in new states. Early detection allows for the infested areas to be quickly quarantined with the intention of slowing the spread of this beetle. After many years of research, the USDA/APHIS developed traps and lures that attract and capture EABs. The large, purple (Figure 2) are placed in in ash trees – high in the canopy of a small tree or on the low branch of a tall tree. A pheromone lure hangs freely at the center of the prismatic trap, and a sticky surface ensnares the beetles.

Following the initial detection of EAB in Michigan, the United States Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA/APHIS) began conducting a survey that has helped detect the EAB in new states. Early detection allows for the infested areas to be quickly quarantined with the intention of slowing the spread of this beetle. After many years of research, the USDA/APHIS developed traps and lures that attract and capture EABs. The large, purple (Figure 2) are placed in in ash trees – high in the canopy of a small tree or on the low branch of a tall tree. A pheromone lure hangs freely at the center of the prismatic trap, and a sticky surface ensnares the beetles.

The Texas EAB survey has been conducted annually since 2008. The Texas Invasive Species Institute has participated in the survey for the past 3 years (2012-2014). In 2013 and 2014, TISI partnered with the Texas A&M Forest Service (TFS) and will do so again in 2015. During the first year, TISI set out 549 traps in 44 counties in east, northeast, southeast, south, west and gulf coast regions of Texas. While setting up these traps, we also increased public awareness about the beetle and thus improved the likelihood of early detection and rapid response to the potential spread of EAB. After the EAB was found in Colorado, the USDA increased their trap quota for the 2014 survey season. In 2014, TISI placed 874 traps in 72 counties located in east, northeast, southeast, panhandle, Edwards plateau, south and gulf coast regions of Texas. In 2015 TISI continued its coordination with TAMU Forest Service and USDA, and placed 403 traps in 50 counties. Although the EAB has yet to be reported in Texas, it has been found in six Arkansas counties. Now, 26 Arkansas counties are quarantined and it is likely that the EAB will soon cross the state line into Texas.

During the 2014 biennial Texas Invasive Pest and Plant Conference, TISI became aware of the Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center’s ash seed banking initiative. Given the threat posed by the emerald ash borer in our neighboring states, the Wildflower Center began collecting ash seeds in Travis and surrounding counties. Because TISI participated in the annual USDA/APHIS-funded EAB survey from 2012-2014, we realized that we could provide map data for the Wildflower Center’s database. Beginning with our 2014 EAB survey, we started collecting ash seeds and provided specimens from 3 ash tree species in 7 counties. TISI will again be a major participant in the 2015 EAB survey and we will to provide map data and ash seeds in collaboration with the Wildflower Center. The Wildflower Center and the Texas Invasive Species Institute both depend on proactive citizens to help us in the fight against invasive species. If you or anyone you know might be interesting in ash seed collection, please send an email with all of your information to ashseed@wildflower.org

During the 2014 biennial Texas Invasive Pest and Plant Conference, TISI became aware of the Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center’s ash seed banking initiative. Given the threat posed by the emerald ash borer in our neighboring states, the Wildflower Center began collecting ash seeds in Travis and surrounding counties. Because TISI participated in the annual USDA/APHIS-funded EAB survey from 2012-2014, we realized that we could provide map data for the Wildflower Center’s database. Beginning with our 2014 EAB survey, we started collecting ash seeds and provided specimens from 3 ash tree species in 7 counties. TISI will again be a major participant in the 2015 EAB survey and we will to provide map data and ash seeds in collaboration with the Wildflower Center. The Wildflower Center and the Texas Invasive Species Institute both depend on proactive citizens to help us in the fight against invasive species. If you or anyone you know might be interesting in ash seed collection, please send an email with all of your information to ashseed@wildflower.org

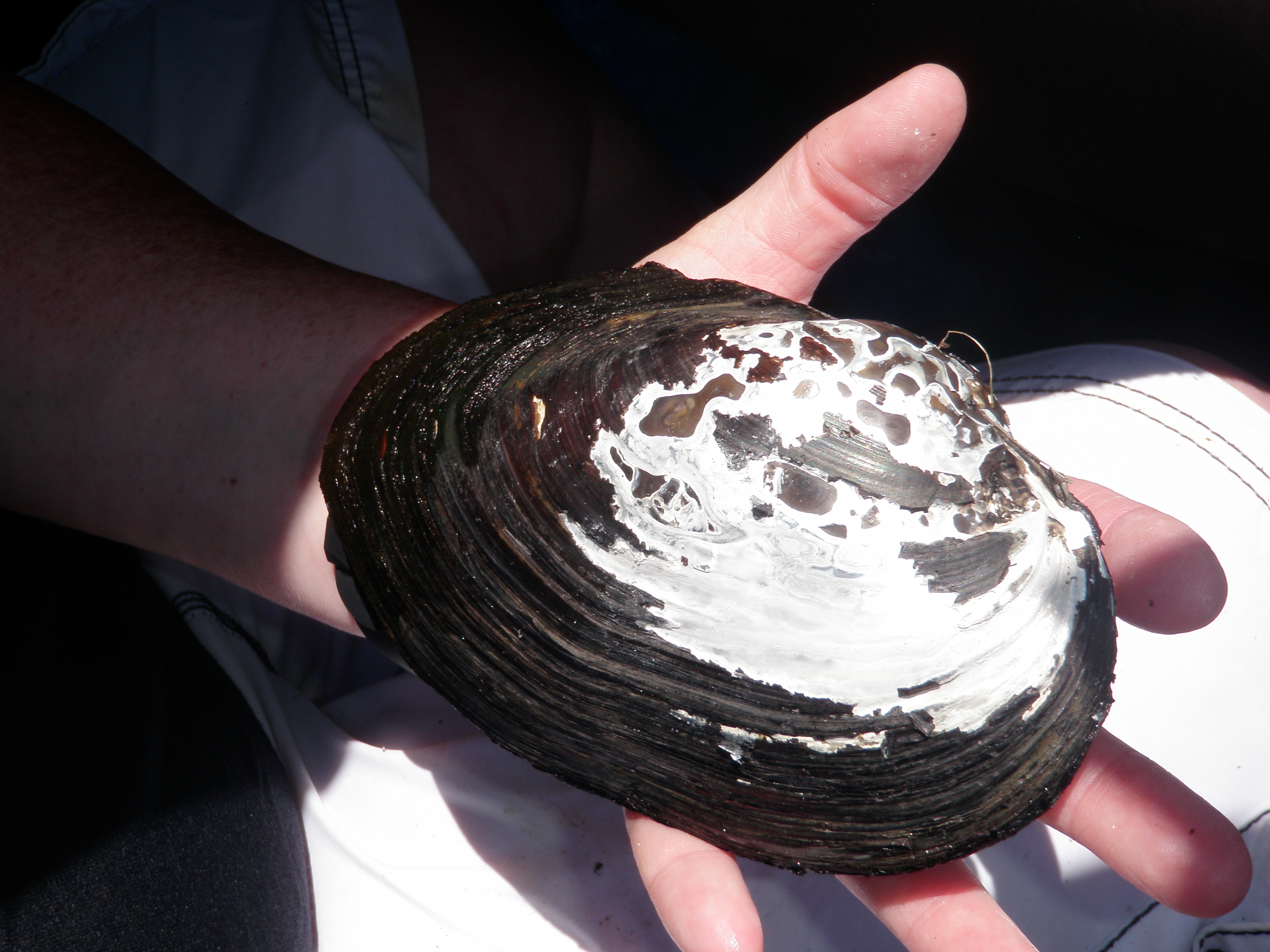

In 2013 the Texas Invasive Species Institute was commissioned to perform water quality and mussel surveys for four Texas Army National Guard bases: Camp Bowie in Brownwood; Camp Maxey north of Paris; Camp Swift in Bastrop; and Fort Wolters in Mineral Wells. Each base was visited three times (August 2013, April 2014, and May 2014) and during the 12 surveys, investigators searched all accessible lakes, ponds, and streams on the four bases. Our goal was to determine presence and relative abundance of freshwater mussels, fingernail clams and two invasive species, Asian clams (Corbicula fluminea) and Zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha), and compare the results to previous surveys. Each site was surveyed to locate living and dead specimens in the various habitat types within each site and water quality parameters including dissolved oxygen, temperature and pH were tested at each sample location. Fortunately, TISI shares a building with the Texas Research Institute for Environmental Studies (TRIES) analytical lab. This lab collaborated with TISI to test for other physicochemical analyses including: turbidity, total solids, total suspended solids, total dissolved solids, conductivity, alkalinity, total coliforms, fecal coliforms and priority pollutants. Measurements of these indicators help establish if a body of water is healthy.

In 2013 the Texas Invasive Species Institute was commissioned to perform water quality and mussel surveys for four Texas Army National Guard bases: Camp Bowie in Brownwood; Camp Maxey north of Paris; Camp Swift in Bastrop; and Fort Wolters in Mineral Wells. Each base was visited three times (August 2013, April 2014, and May 2014) and during the 12 surveys, investigators searched all accessible lakes, ponds, and streams on the four bases. Our goal was to determine presence and relative abundance of freshwater mussels, fingernail clams and two invasive species, Asian clams (Corbicula fluminea) and Zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha), and compare the results to previous surveys. Each site was surveyed to locate living and dead specimens in the various habitat types within each site and water quality parameters including dissolved oxygen, temperature and pH were tested at each sample location. Fortunately, TISI shares a building with the Texas Research Institute for Environmental Studies (TRIES) analytical lab. This lab collaborated with TISI to test for other physicochemical analyses including: turbidity, total solids, total suspended solids, total dissolved solids, conductivity, alkalinity, total coliforms, fecal coliforms and priority pollutants. Measurements of these indicators help establish if a body of water is healthy.

The last surveys at these National Guard bases were conducted in 2003, 2004 and 2006. The survey data collected by TISI in 2013 and 2014 indicated that mussel richness (i.e., number of species present) and abundance had declined. For example, where nine species of bivalves were found at Camp Swift in the 2003-2004 surveys, only four species were collected in 2013-2014. The Asian clam, an invasive species, was the only bivalve present at three of the sites TISI surveyed. In addition to the Asian clam, TISI found the giant floater (Pyganodon grandis), fingernail clams (Spaeium partumeium and S. transverum), and pondhorn mussel (Uniomerus tetralasmus) at Camp Swift. Additionally, some water parameters that normally indicate aquatic health were extremely low.

The last surveys at these National Guard bases were conducted in 2003, 2004 and 2006. The survey data collected by TISI in 2013 and 2014 indicated that mussel richness (i.e., number of species present) and abundance had declined. For example, where nine species of bivalves were found at Camp Swift in the 2003-2004 surveys, only four species were collected in 2013-2014. The Asian clam, an invasive species, was the only bivalve present at three of the sites TISI surveyed. In addition to the Asian clam, TISI found the giant floater (Pyganodon grandis), fingernail clams (Spaeium partumeium and S. transverum), and pondhorn mussel (Uniomerus tetralasmus) at Camp Swift. Additionally, some water parameters that normally indicate aquatic health were extremely low.

Melissa Sisson and Dr. Brian Chapman prepared the 2013-2014 survey reports and offered potential explanations for the mussel decline in addition to management strategies for improving recruitment native freshwater mussels while controlling Asian clam populations. Suggested management strategies included removing deep deposits of fine silt and ooze from the ponds because it creates an anaerobic environment within the sediments that limits the survival of juvenile mussels. Planting low-growing, aquatic vegetation along the shorelines of ponds with no vegetation would control erosion, absorb heavy metals, and provide cover and substrate for juvenile mussels and fingernail clams.

The United States Geological Survey noticed a die off between the two migratory water fowl species, the black brant (Branta bernicla nigricans) and the greater white-fronted goose (Anser albifrons), that might be attributed to climate change in their migratory habitats. The USGS wanted to determine whether climate change caused the die offs or if some internal factor, such as parasite infestations, may have playing a role. Helminth parasites are often referred to as “worms”

The United States Geological Survey noticed a die off between the two migratory water fowl species, the black brant (Branta bernicla nigricans) and the greater white-fronted goose (Anser albifrons), that might be attributed to climate change in their migratory habitats. The USGS wanted to determine whether climate change caused the die offs or if some internal factor, such as parasite infestations, may have playing a role. Helminth parasites are often referred to as “worms”  and may include such groups as nematodes, trematodes and cestodes.For the survey the USGS collected specimens of both avian species, froze them immediately, and sent to them the Texas Invasive Species Institute. At TISI, the birds were necropsied and all helminth parasites were extracted and identified. The USGS will determine if there is a correlation between severe helminth infection and the increase observed in mortality rates in the two waterfowl species. It is important to know which helminthes are causing the most damage to the hosts and if the two waterfowl species share parasite infections. Once the parasitic worms are identified, TISI will provide information on the parasite lifecycles and how the waterfowl might be contracting them. Such Information will help the USGS in their attempts protect the waterfowl species by eliminating parasite transmission pathways. If a parasite’s life cycle is interrupted, it cannot infect other waterfowl hosts or persist in the environment. Necropsy of the birds is still continuing at a TISI laboratory led by Dr. Autumn Smith-Herron, and once all of the data is gathered, it will be sent to the USGS with appropriate management suggestions.

and may include such groups as nematodes, trematodes and cestodes.For the survey the USGS collected specimens of both avian species, froze them immediately, and sent to them the Texas Invasive Species Institute. At TISI, the birds were necropsied and all helminth parasites were extracted and identified. The USGS will determine if there is a correlation between severe helminth infection and the increase observed in mortality rates in the two waterfowl species. It is important to know which helminthes are causing the most damage to the hosts and if the two waterfowl species share parasite infections. Once the parasitic worms are identified, TISI will provide information on the parasite lifecycles and how the waterfowl might be contracting them. Such Information will help the USGS in their attempts protect the waterfowl species by eliminating parasite transmission pathways. If a parasite’s life cycle is interrupted, it cannot infect other waterfowl hosts or persist in the environment. Necropsy of the birds is still continuing at a TISI laboratory led by Dr. Autumn Smith-Herron, and once all of the data is gathered, it will be sent to the USGS with appropriate management suggestions.

The Tawny Crazy Ant (Nylanderia fulva) is an invasive species that is native to Brazil. It was first discovered in the United States near Houston, Texas in 2002. The ant quickly became a problem for local residents and businesses when it began invading homes and destroying electrical work. Dr. Danny McDonald, the director of the TRIES Invertebrate Toxicology Lab, has been researching the invasive tawny crazy ant for the past several years. When it was

The Tawny Crazy Ant (Nylanderia fulva) is an invasive species that is native to Brazil. It was first discovered in the United States near Houston, Texas in 2002. The ant quickly became a problem for local residents and businesses when it began invading homes and destroying electrical work. Dr. Danny McDonald, the director of the TRIES Invertebrate Toxicology Lab, has been researching the invasive tawny crazy ant for the past several years. When it was  discovered in Harris County, Texas, very little was known about the ant’s life history. Dr. McDonald has received several grants that have allowed him to conduct an intense studies of the tawny crazy ant to determine its reproductive patterns, habitat preferences, and distribution. It has been found as far west as Bexar County, as far south as Hidalgo County, as far north as San Augustine and as far east as Orange County. In 2013, funding from Central Life Sciences allowed TRIES to test certain pesticides in an effort to determine which were most effective in eliminating tawny crazy ants. In 2014, he was also approached by other pesticide manufactures (Bayer, BASF and Neudorff) to test the effectiveness of their products on the tawny crazy ant. His continuing research has helped establish the distribution and life history of this ant while also figuring out which strategies are best used for management practices.

discovered in Harris County, Texas, very little was known about the ant’s life history. Dr. McDonald has received several grants that have allowed him to conduct an intense studies of the tawny crazy ant to determine its reproductive patterns, habitat preferences, and distribution. It has been found as far west as Bexar County, as far south as Hidalgo County, as far north as San Augustine and as far east as Orange County. In 2013, funding from Central Life Sciences allowed TRIES to test certain pesticides in an effort to determine which were most effective in eliminating tawny crazy ants. In 2014, he was also approached by other pesticide manufactures (Bayer, BASF and Neudorff) to test the effectiveness of their products on the tawny crazy ant. His continuing research has helped establish the distribution and life history of this ant while also figuring out which strategies are best used for management practices.

Both the Northern Bobwhite Quail (Colinus virginianus) and the Scaled Quail (Callipepla squamata) are native to Texas with the former having a southeastern distribution and the latter having a southwestern distribution. In Central Texas, from Hidalgo County up through the Panhandle, both species may occur in the same area. Bobwhite quail has been a bird hunter’s favorite in Texas for many years and has been continuously studied. When biologists at Texas A&M-Kingsville started noticing severe population declines of bobwhites, this became cause for concern, not only because it was a game species, but because some populations almost disappearing altogether. Many recent studies have shown that the bobwhites contract an eye nematode, Oxyspirura petrowi, that could have a

Both the Northern Bobwhite Quail (Colinus virginianus) and the Scaled Quail (Callipepla squamata) are native to Texas with the former having a southeastern distribution and the latter having a southwestern distribution. In Central Texas, from Hidalgo County up through the Panhandle, both species may occur in the same area. Bobwhite quail has been a bird hunter’s favorite in Texas for many years and has been continuously studied. When biologists at Texas A&M-Kingsville started noticing severe population declines of bobwhites, this became cause for concern, not only because it was a game species, but because some populations almost disappearing altogether. Many recent studies have shown that the bobwhites contract an eye nematode, Oxyspirura petrowi, that could have a negatively effect on populations. Oxyspirura petrowi was initially described in 1929, but very little was known about the life cycle of the parasite or the impact it has on bobwhite quail.

negatively effect on populations. Oxyspirura petrowi was initially described in 1929, but very little was known about the life cycle of the parasite or the impact it has on bobwhite quail.

Recent studies have been able to demonstrate a correlation between bobwhite population decline and eye worm infection. Oxyspirura petrowi lives on the surface of the eyeball or behind it in the lacrimal duct and associated glands. Since the two species of quail have an overlap in distribution in some areas, parasitological surveys of scaled quails were initiated and they were also infected with the eye worm.

In order to confirm the pathology of the eye worm on the both quail species, histological techniques must be applied. Histology is the study of cell anatomy and tissues of plants and animals, and it can be used to observe the pathology of a disease and its impact on cells and tissues. Dr. Autumn Smith-Herron was commissioned by Texas A&M Kingsville to help with their studies of northern bobwhite and scaled quail. For the past two years she has helped train Texas A&M-Kingsville students, and performed histopathological examinations of bobwhite quail eyes. By education and training students, she has enabled others to perform histopathological studies of an important parasite and develop information about the physical toll this nematode has on its hosts. The parasite causes damage to the tissues behind the eyeball as well as hemorrhaging and swelling that applies pressure to the optic nerve. These symptoms can render the bird practically blind and severely compromise its ability to survive in the wild. Recently, Dr. Smith-Herron received samples of scaled quail intestines for a study of their histopathology. The intestinal tissues are currently being processed. Once the tissues are analyzed, they may provide insights about the impact that the intestinal nematodes might have on quail populations and present options for management strategies.

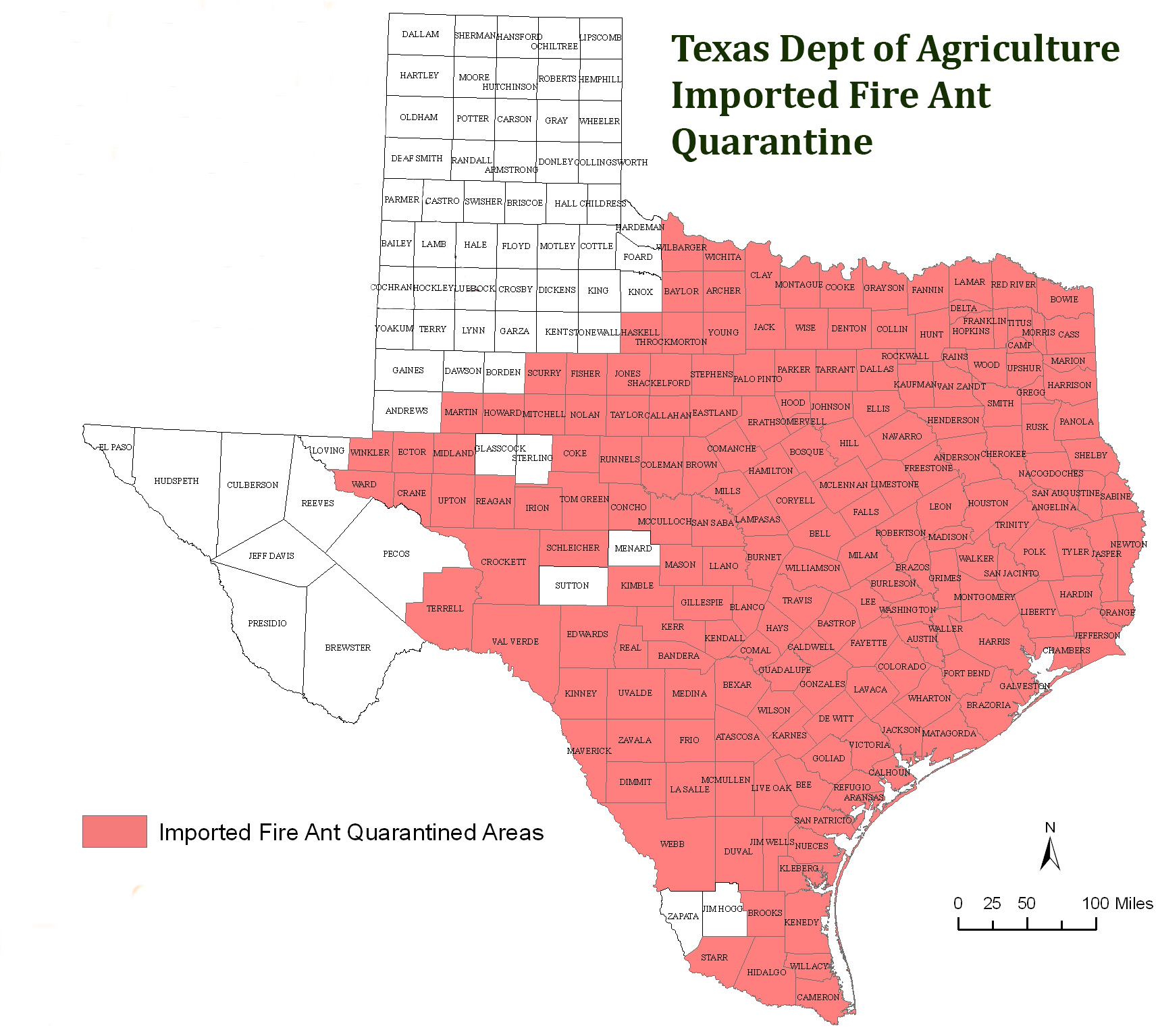

The red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) is an urban, agricultural and wildlife pest that is native to South America. It was first introduced in the 1930’s and has spread to 9 southeastern states and infests over 260 million acres. The species reproduces and spreads quickly, displacing several native ant species such as Harvester ants (Polygomyrmex sp.) and Texas leafcutting ants (Atta texana). In Texas alone, this ant is estimated to have over a $1 billion impact. The red imported fire ant has been present in Texas for over 80 years and it is present in all but 60 counties. Each county where it is found is placed under quarantine in an attempt to manage this fiercely invasive insect. However, the ant continues to widen its distribution, so the Texas Department of Agriculture commissions labs to help with their annual RIFA survey. In 2013 and 2014, Dr. Danny McDonald was commissioned for the survey. In 2013 Dr. McDonald, and some members of TISI, traveled all over west Texas and the Edwards Plateau and found the fire ants in 3 new counties. For 2014, Dr. McDonald traveled to the same regions and found another 3 counties to add to the RIFA distribution. In total 6 counties (represented by yellow stars on the map) were added: Jim Hogg, Knox, Menard, Sterling, Stonewall and Sutton. By conducting this annual survey the Texas Department of Agriculture hopes to be able to apply management strategies to control populations in newly established counties.

The red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) is an urban, agricultural and wildlife pest that is native to South America. It was first introduced in the 1930’s and has spread to 9 southeastern states and infests over 260 million acres. The species reproduces and spreads quickly, displacing several native ant species such as Harvester ants (Polygomyrmex sp.) and Texas leafcutting ants (Atta texana). In Texas alone, this ant is estimated to have over a $1 billion impact. The red imported fire ant has been present in Texas for over 80 years and it is present in all but 60 counties. Each county where it is found is placed under quarantine in an attempt to manage this fiercely invasive insect. However, the ant continues to widen its distribution, so the Texas Department of Agriculture commissions labs to help with their annual RIFA survey. In 2013 and 2014, Dr. Danny McDonald was commissioned for the survey. In 2013 Dr. McDonald, and some members of TISI, traveled all over west Texas and the Edwards Plateau and found the fire ants in 3 new counties. For 2014, Dr. McDonald traveled to the same regions and found another 3 counties to add to the RIFA distribution. In total 6 counties (represented by yellow stars on the map) were added: Jim Hogg, Knox, Menard, Sterling, Stonewall and Sutton. By conducting this annual survey the Texas Department of Agriculture hopes to be able to apply management strategies to control populations in newly established counties.

LITERATURE CITED

Dunham, N. R., Soliz, L. A., Fedynich, A. M., Rollins, D., & Kendall, R. J. (2014). EVIDENCE OF AN OXYSPIRURA PETROWI EPIZOOTIC IN NORTHERN BOBWHITES (COLINUS VIRGINIANUS), TEXAS, USA. Journal of wildlife diseases.

McClure, H. E. (1949). The Eyeworm, Oxyspirura petrowi, in Nebraska Pheasants. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 304-307.

McDonald, D. L. (2012). Investigation of an Invasive Ant Species: Nylanderia fulva Colony Extraction, Management, Diet Preference, Fecundity, and Mechanical Vector Potential (Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University).

Villarreal, S. M., Fedynich, A. M., Brennan, L. A., & Rollins, D. (2012). Parasitic eyeworm Oxyspirura petrowi in northern bobwhites from the Rolling Plains of Texas, 2007–2011. In Proceedings of the National Quail Symposium (Vol. 7, pp. 241-243).

Xiang, L., Guo, F., Zhang, H., LaCoste, L., Rollins, D., Bruno, A., ... & Zhu, G. (2013). Gene discovery, evolutionary affinity and molecular detection of Oxyspirura petrowi, an eye worm parasite of game birds. BMC microbiology, 13(1), 233.