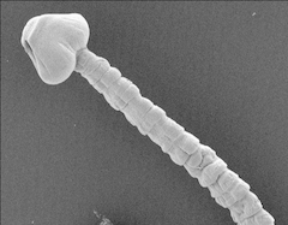

Photographer: Dr. Boris Kuperman and Dr. Victoria Matey Source: www.nas.er.gov/queries/GreatLakes/SpeciesInfo

The Asian tapeworm (Bothriocephalus acheilognathi) can be identified by the scolex shaped like an arrow head with a terminal disc that is undeveloped. There are two anterolateral bothria on the scole with proglottids directly behind the scolex.

Symptoms: Intestinal inflammation, protein depletion, altered digestive enzyme activity, anemia, reduced growth, temperature-dependent mortality, and reduced ability to cope with stressors.

Hosts: Cyprinids (carps, minnows, etc.) and other freshwater fish

Bothriocephalus acheilognathi is a hearty parasite as a host generalist which allows it to infect several different host species and become established in various areas. Some endangered species such as the humpback chub (Gila cypha) and Mojave tui chub (Siphantes bicolor mohavensis) have been infected, which provides another threat to the decreasing populations. This tapeworm threatens conservation efforts on several other species of federally endangered fish as well.

The Asian tapeworm has a simple lifecycle relative to other tapeworms with one intermediate host and a definitive host. Copepods serve as intermediate hosts and freshwater fish are definitive hosts. In the adult stage the asian tapeworm attaches to the host gut tegument and feeds off of the nutrients intended for the host. This tapeworm is hemaphroditic and produces zygotes that have been self fertilized. With a low host specificity the asian tapeworm is able to infect fish species from 12 families and 6 orders across the world.

Introduction of B. acheilognathi most likely occurred via bait fish, such as the grass carp, a native host to this tapeworm. Undetected transfer occurred throughout the United States with widespread reports of infected fish in the wild.

Native Origin: East Asia

U.S. Habitat: Typically found in the host or in freshwater free swimming larval stage with water temperature from 28-31C.

U.S. Present: AR, AZ, CA, CO, HI, MI, NC, NM, NV, OK, TX, UT

Texas: Pecos River, Rio Grande River, San Jacinto watershed, San Juan watershed, Santa Ana watershed, Santa Clara watershed, and Santa Margarita watershed

References

Bean, M. G. 2008. Occurence and impact of the Asian fish tapeworm Bothriocephalus acheilognathi in the Rio Grande (Rio Bravo del Norte). MS Thesis. Texas State University, San Marcos.

Bean, M. G., A. Skerikova, T. H. Bonner, T. Scholz, and D. G. Huffman. 2007. First record of Bothriocephalus acheilognathi in the Rio Grande with comparative analysis of ITS2 and V4-18S rRNA gene sequences. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 19: 71-76.

Choudhury, A., E. Charipar, P. Nelson, J. R. Hodgson, S. Bonar, and R. A. Cole. 2006. Update on the distribution of the invasive Asian fish tapeworm, Bothriocephalus acheilognathi, in the U.S. and Canada. Comparative Parasitology 73(2): 269-273.

Heckmann, R. A., P. D. Greger, and R. C. Furtek. 1993. The Asian fish tapeworm, Bothriocephalus acheilognathi, in fishes from Nevada. Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington 60(1): 127-128.

McAllister CT, Bursey CR, Fayton TJ, Connior MB, Robison HW. 2015b. First report of the Asian fish tapeworm, Bothriocephalus acheilognathi (Cestoidea: Bothriocephalidea:Bothriocephalidae) from Oklahoma with new host records in non-hatchery fishes in Arkansas. Proc. Okla. Acad. Sci. 95:35–41.

Pool, D. W. 1987. A note on the synonomy of Bothriocephalus acheilognathi Yamaguti, 1934, B. aegyptiacus Rysavy and Moravec, 1975 and B. kivuensis Baer and Fain, 1958. Parasitology Research 73: 146-150.

Internet Sources